Ah … We work together? The Ringelmann effect

We have always thought that, Aristotelian, the result of the sum of the action of several individuals was certainly and always better than the performance of the individual.

Well, that’s not necessarily the case. And I’ll show you why.

Some suspicions should come to us thinking about the very famous law of software development called Brook’s law: adding resources to a late project increases / worsens the delay. But so we still remain on the qualitative.

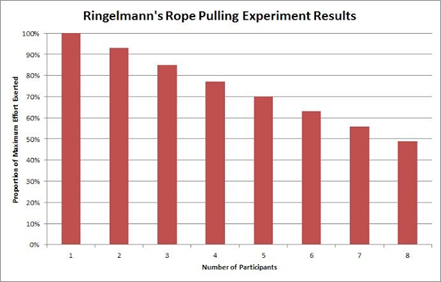

In 1913 Maximilien Ringelmann, a French agricultural engineer, published a study that went down in history. Ringelmann carries out a series of experiments, showing that in tug-of-war, by increasing the number of big men who pull, the overall force on the rope expressed by each is a fraction of that expressed by the individual. Moreover. The greater the number of shooters, the lower the individual quota with respect to the single performance. Visually, the strength decreased by almost 10% with each addition. Ringelmann, as a good engineer, thought that the reason was due to a dispersion of effort deriving from the greater difficulty of coordination between the members of the group.

In the seventies and on several occasions, this idea was studied and re-studied and, above all, applied to areas where not only physical but also cognitive activity was at stake. Whether it was tug-of-war or brainsotrming, practically all the authors confirmed that, as the number of members of a group increased, the performance decreased!

In fact, a few years after Ringelmann (in 1926), Otto Koehler makes a similar experiment and points out that, yes, in large groups the Ringelmann effect may be true, but in small groups, from two to four components, the action of group, on the other hand, multiplies the performance of the individual. Koehler explained this using the idea of motivation: in a highly visible social context (the small group) all the participants in the action feel motivated to give their best and therefore performance improves. This study goes unnoticed after all.

As I told you, the Ringelmann effect becomes a star of social studies to the point of being considered a form of social disease, social loafing, which undermines all forms of large-scale human collaboration.

The ‘sucker effect’ is found experimentally and even measured: the members of a team in which social loafing begins to manifest themselves begin to feel that they are ‘the most foolish’ and give up their commitment in turn. The result on the performance of the group is catastrophic!

But the researchers did not give up, for twenty years, from the 1980s to the early 2000s, the studies followed one another trying to identify corrective measures that can remedy this social scourge: laziness.

Ah, but I was missing a piece.

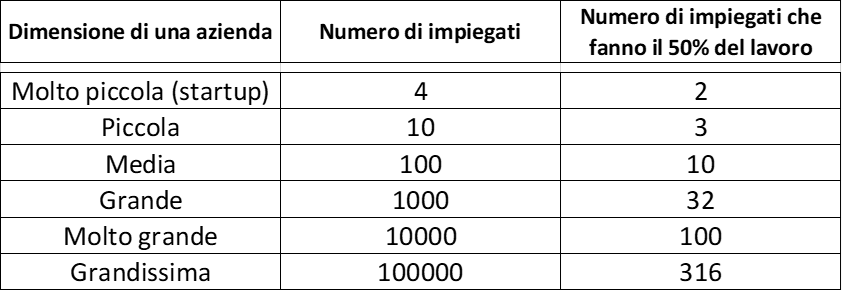

In the mid-1960s, an English researcher and scientist, Derek Price, during a statistical research on scientific publications, realizes that there is an important correlation between the number of studies published on a topic and the number of authors who have published them. produce. In fact, 50% of the total number of studies is produced by the square root of the total number of authors.

Seen in this way it seems a harmless law. But it is quickly adopted to philosophize about all intellectual production and then becomes a panacea for business literature. The result is very interesting. Look at this table.

Strong, right? 100 would work for 10,000… Too bad it’s an extrapolation, neither more nor less like the Pareto rule. Yet… it is used in team sizing.

Let’s go back to our scientists and researchers. One after the other, research shows that there are factors that are able to reduce the effect of social loafing and therefore to increase the yield of the contribution of the individual.

Here are some conclusions in a nutshell:

- Improving coordination, opportunities for interdependence, comparison, the quality of exchanges between people: all this improves performance and makes teamwork more effective than the simple sum of individuals.

- The Ringelmann effect is positively correlated to the performance and resistance that participants retain for subsequent performances. In other words, people tend to spare their strength and effort for those performances they will do on their own in conditions of greater visibility.

- Social loafing is significantly reduced when people are given the opportunity to self-assess their performance and measure its effectiveness. In other words, by humanizing and transforming the activity into learning, the multiplication of the performance takes place!

- The perception of the uniqueness of one’s performance or the usefulness of one’s performance drastically reduces the Ringelmann effect.

- Fatigue and tiredness also affect the Ringelmann effect, and, as you can imagine, increase it!

So what?

Research shows that social loafing is not a bad behavior in itself, but a form of defense that people put in place when they lose the perception that their business is distinctive and meaningful. Let’s be clear: the theme of coordination exists and has its effect, but it is not enough to make a team work.

So the Koehler effect can win over the Ringelmann effect !!!

That’s why with Paolo Chinetti we wrote “the Right Team”!